Arthur Miller’s dramatization of the Salem witch trials has rarely if ever seemed as timeless or proven as powerful as it does in The Antaeus Company’s stunning new revival of the 1953 classic The Crucible, brilliantly directed by Armin Shimerman and Geoffrey Wade.

Wade’s program note explains the directors’ concept as follows: “This production is set in a sort of ‘non-time,’ where a group of people come together to tell this story in a stripped-down, unapologetically theatrical style hoping you will hear this oft-told tale in a fresh, new, intriguing way.”

The “non-time” Wade is referring to becomes clear from our first glance at E.B. Brooks’ costumes, outfits which suggest some non-specific “past tense,” yet could, as per the directors’ and designer’s intentions, be worn to the nearby Starbucks without provoking much curiosity or even a passing glance.

Having already assembled onstage during pre-show announcements, the cast begin Miller’s play by joining hands in a circle to sing John Allee’s adaptation of the 1649 Bay Psalm Book’s “Therefore Shall Not Ungodly Men.” These seventeen actors are the “group of people come together to tell this story,” and tell it they will, though not as you have ever seen it told before.

First and foremost, sequences involving large groups of characters are played with actors facing the audience. Not only does this unorthodox approach pull us into the story by making us the characters being spoken to, it allows us to be both cinematographer and editor as our eyes move from close-up to close-up, able at any time to see each actor’s facial expressions and reactions head-on. Only the play’s more intimate scenes, those between two (or a small number of) characters making authentic personal connections, are performed traditionally. And regardless of how each scene is being played, carefully chosen groups of actors remain standing or seated upstage to witness the action unfolding before them.

This non-traditional, “non-time” approach allows for casting choices that a more standard approach would rule out. Several male roles are played by female actors, and colorblind casting allows for actors of color to portray roles they might not normally be assigned.

Shimerman and Wade are well-aware that this off-beat telling of Miller’s sixty-year-old play may alienate a certain number of audience members. Most will, I believe, be drawn into The Crucible as never before.

Miller’s characters remain as written back in 1953, beginning with Reverend Samuel Parris (Allee and Joe Delafield alternating in this “partner-cast” production), a man living in constant fear that his “many enemies” will drive him from his pulpit. At lights up, the hellfire-and-damnation preacher’s daughter Betty (Eva Beebe/Ranya Jaber) lies in bed, nearly comatose, and Parris soon learns that she and some other local girls have been out all night committing the sin of dancing in the forest, and perhaps worse.

The girls’ apparent leader, concupiscent Abigail Williams (Nicole Erb/Kate Maher), asserts that “there be no blush about my name,” yet eight months ago she was dismissed from her job at the home of John Proctor (Bo Foxworth/Christopher Guilmet) and his wife Elizabeth (Kimiko Gelman/Devon Sorvari) following Elizabeth’s discovery of John and Abby’s clandestine affair.

Meanwhile, Mrs. Ann Putnam (Rhonda Aldrich/Lily Knight) has begun to suspect elderly midwife Rebecca Nurse (Fran Bennett/Dawn Didawick) of being an agent of Satan and the cause of her string of seven miscarriages. Mrs. Putnam’s husband Thomas (Stephen Mendel/Stoney Westmoreland) advises Reverend Parris to “strike out against the devil, and the town will bless you for it.”

The best defense against his waning popularity being a good offence, Parris decides to take Thomas’ advice. In this, he is aided and abetted by Abigail who, having seen her parents killed by Indians, fears nothing but the loss of her lover, John Proctor, and if accusing Elizabeth of witchcraft is the only way to get back into John’s bed, then accuse she will.

Though Rebecca warns that “there is prodigious danger in the seeking of loose spirits,” Parris goes ahead and summons witchcraft authority Reverend Hale (Ann Noble/John Prosky), and the hunt is on. “The town’s gone wild,” declares a fearful Elizabeth, predicting rightly that the accused “will hang for witchcraft.”

Only Elizabeth and John seem to understand that this so-called “witchcraft” is a fraud, but who will believe them? “The girl’s a saint now,” says John of Abigail, and anyone who dares to doubt her is sure to be her next victim.

By this point, parallels between the 1692-93 Salem Witch Trials and the 1950-56 McCarthy Witch Hunt will have become clear to those familiar with mid-20th Century American history, since regardless of whether it is witches or communists being stalked, the fastest way to be exonerated is to point one’s finger at others, no matter how innocent they may be. Adding to its impact on contemporary audiences is The Crucible’s palpable indictment of religious fanaticism gone amok, for none of this would be happening were religious leaders and judges using their heads rather than dogma and blindly accusing anyone who doubts the veracity of Abigail’s accusations of being in league with the devil. (The mere reading of books is considered a sign of Satan, a notion which today’s Sarah Palin and her acolytes would probably find spot-on.)

Though Reverend Hale eventually proves sharp enough to recognize the truth, by then it is too late, for the judges in charge of the trials, particularly Deputy-Governor Danforth (James Sutorius/Reba Waters Thomas), refuse to stop the proceedings for no reason other than because this would mean admitting having been wrong from the start. (Sound familiar?)

Arthur Miller’s brilliance as a playwright has never been more evident than in The Crucible, for despite dialog that sounds stilted to modern ears (“I never kept no poppets, not since I were a girl”), the historical characters whom the play depicts are as contemporary as those in his modern dramas (Death of a Salesman, All My Sons, etc.) and every bit as compelling. Despite knowing the play’s outcome, the audience cannot help hoping that somehow, someone in power will see the girls’ “pretense,” and end this murderous witch hunt.

The Antaeus Company may have adopted “partner casting” for practical reasons, the better to allow company members to accept short-term paying jobs in film and TV while remaining in a production throughout its run, regardless of their reasons, the resulting productions are theatrical manna for L.A. theater fans, allowing weekend audiences to see two often startlingly different ensembles while weeknight audiences are treated to combinations of both.

Having seen both “The Proctors” and “The Putnams,” I can assure you that each cast is filled to the brim with outstanding, often inspired acting, and that whichever cast (or the Thursday/Friday “Poppets”) you elect to see, you will be guaranteed one superb performance after another, though often startlingly different ones.

Take, for instance, Foxworth’s Thomas Jefferson of a John Proctor vs. Guilmet’s Abe Lincoln-as-17th Century colonial, or Erb’s wronged victim of an Abby vs. Maher’s icy seductress. Delafield plays Reverend Parris as boy-next-door turned religious fanatic, while Allee’s is bullied adolescent turned bully. Bennett’s Rebecca Nurse carries the wisdom of the ages with her while Didawick’s wisdom if of a considerably folksier variety. And these are just a few examples of how night-and-day different two actors can make a single role. As for the gender-bending Reverends Hale and Judges Danforth, it is not that Noble and Thomas are female actors playing male roles. Rather, each plays her part as a woman, and never more clearly than when Noble’s Jean Hale breaks down into tears as Prosky’s John Hale never would.

Completing these all-around superb casts are Marcia Batisse and Saundra McClain as Tituba and Judge Hathorne, Morgan Marcell and Rachel Berney Needleman as Mercy Lewis, Shannon Lee Clair and Alexandra Goodman as Mary Warren, Steve Hofvendahl and Phil Proctor as Giles Corey, William C. Mitchell and Joseph Ruskin as Francis Nurse, Jim Kane and R. Scott Thompson as Ezekiel Cheever, and Daniel Dorr and Aaron Lyons as Marshall Herrick.

Special mention must be made of teen and preteen accusers Abby, Betty, Mercy, and Mary, whose courtroom hysteria packs a gut-punching emotional wallop, and note should be made too of the much-needed comic relief provided by the quirky duo of Hofvendahl and Proctor as eternal plaintiff Giles. As for John and Elizabeth’s final moments together, whether it is Guilmet and Sorvari you are seeing or Foxworth and Gelman, prepare to be moved to the very depths of your soul.

In addition to costume designer Brooks’ bevy of striking, earth-toned “non-time” outfits, superlatives are in order for Stephen Gifford’s starkly stunning scenic design, Bosco Flanagan’s strikingly dramatic lighting design, and production manager Adam Meyer’s meticulously detailed properties design, with special snaps to Jeff Gardner for his impact-enhancing sound design with his suspenseful rumbles and peals of thunder.

Joanna Syiek is assistant director, Morgan DeGroff is assistant costume designer, and Thompson is technical director. Kimberly Weber is production stage manager and Kristin Weber assistant stage manager. Bill Brochtrup, Rob Nagle, and John Sloan are Antaeus Company co-artistic directors; Shimerman and Kitty Swink are associate artistic directors.

On an entirely personal note, this reviewer made his stage debut as a Samohi senior playing Reverend Parris opposite classmate Shimerman’s John Proctor. It was not until decades later that I finally saw The Crucible onstage for the first time, and since then I have seen three additional productions, the current Antaeus Company revival the hands-down finest of the bunch. Audiences willing to go on the unconventional journey undertaken by Shimerman and Wade and their remarkable casts will be richly rewarded.

The Antaeus Company, 5112 Lankershim Blvd., North Hollywood.

www.Antaeus.org

–Steven Stanley

May 16 & 17, 2013

Photos:

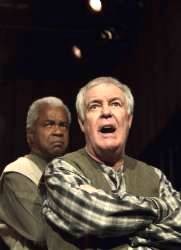

(l.) The Proctors, by Karianne Flaathen

(r.) The Putnams, by FacetPhotography.com

Tags: Arthur Miller, Los Angeles Theater Review, The Antaeus Company

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2025 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2025 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY