Epic in scope. As cinematic as it is theatrical. A lesson in history and a cautionary tale for future generations. Tim Morton-Smith’s monumental bio-drama Oppenheimer is all this and a spectacular achievement for Rogue Machine Theatre in its American Premiere.

J. Robert Oppenheimer (James Liebman) may be best known today as “The Father Of The Atomic Bomb” but when recruited to head the U.S. government’s Manhattan Project in 1939, he is simply “Oppie,” a 34-year-old theoretical physicist leading a quiet life as a U.C. Berkeley professor with a fashionably leftist-leaning circle of family and friends.

These include his younger brother Frank (Ryan Brophy) and sister-in-law Jackie (Miranda Wynne), close friend and protege Robert Serber (Mark Jacobson) and his wife Charlotte (Jennifer Pollono), fellow physicists Richard Feynman (Brady Richards), Giovanni Rossi Lomanitz (Kenney Selvey), and Joe Weinberg (Brewster Parsons), novelist Haakon Chevalier (Scott Victor Nelson), and Oppie’s mistress Jean Tatlock (Kirsten Kollender).

These include his younger brother Frank (Ryan Brophy) and sister-in-law Jackie (Miranda Wynne), close friend and protege Robert Serber (Mark Jacobson) and his wife Charlotte (Jennifer Pollono), fellow physicists Richard Feynman (Brady Richards), Giovanni Rossi Lomanitz (Kenney Selvey), and Joe Weinberg (Brewster Parsons), novelist Haakon Chevalier (Scott Victor Nelson), and Oppie’s mistress Jean Tatlock (Kirsten Kollender).

Then comes the day Albert Einstein (Ron Bottitta) warns President Franklin D. Roosevelt of the threat posed by German scientists working on the development of a bomb that could flatten an entire city, followed by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and the U.S, government comes knocking on Oppie’s door.

Before long, an international team has been assembled by General Leslie Groves (Bottitta), one that includes physicists Hans Bethe (Michael Redfield), Edward Teller (Dan Via), and Robert Wilson (Zachary Grant), and the clock starts ticking down towards the moment that one side or the other destroys a major population center and ends the war, for better or for worse.

Before long, an international team has been assembled by General Leslie Groves (Bottitta), one that includes physicists Hans Bethe (Michael Redfield), Edward Teller (Dan Via), and Robert Wilson (Zachary Grant), and the clock starts ticking down towards the moment that one side or the other destroys a major population center and ends the war, for better or for worse.

Along the way, Oppie trades in the increasingly mentally disturbed Jean for the equally beautiful but no more stable Kitty Harrison (Rachel Avery), a marriage likely to prove considerably less successful than his efforts to build a bomb.

Along the way, Oppie trades in the increasingly mentally disturbed Jean for the equally beautiful but no more stable Kitty Harrison (Rachel Avery), a marriage likely to prove considerably less successful than his efforts to build a bomb.

One of Oppenheimer’s many virtues is just how clearly playwright Morton-Smith manages to explain nuclear fission to laymen’s ears. Another is how adeptly the English writer alternates between historical events and the intimate lives of those making history.

Yet another is Oppenheimer’s juxtaposition of scenes involving the stage equivalent of “a cast of thousands” with memorable solo moments: Oppie’s metaphorical lecture on chain reaction, a joke whose humor only Hungarians can appreciate, a suicide victim’s heartbreaking soliloquy, Little Boy’s (Sophie Pollono) description of the horrors wreaked on Hiroshima, and Oppie’s final thoughts on being a Destroyer Of Worlds.

Yet another is Oppenheimer’s juxtaposition of scenes involving the stage equivalent of “a cast of thousands” with memorable solo moments: Oppie’s metaphorical lecture on chain reaction, a joke whose humor only Hungarians can appreciate, a suicide victim’s heartbreaking soliloquy, Little Boy’s (Sophie Pollono) description of the horrors wreaked on Hiroshima, and Oppie’s final thoughts on being a Destroyer Of Worlds.

Director John Perrin Flynn proves himself more than up to the task of helming sixty-two scenes, two-dozen players, and a three-hour running time, none of which ever feels like too much.

Director John Perrin Flynn proves himself more than up to the task of helming sixty-two scenes, two-dozen players, and a three-hour running time, none of which ever feels like too much.

A number of sequences stand out: a cocktail party featuring virtually the entire cast, soldiers assembled to watch the first bomb test at Los Alamos, the explosion itself, the drum-beat-fueled post-Hiroshima celebration, and more.

A number of sequences stand out: a cocktail party featuring virtually the entire cast, soldiers assembled to watch the first bomb test at Los Alamos, the explosion itself, the drum-beat-fueled post-Hiroshima celebration, and more.

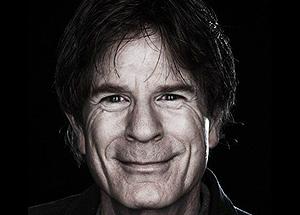

Perhaps not surprisingly, Liebman’s warts-and-all star turn as Oppie is the evening’s standout, a man forced to live the remaining twenty-two years of his life with the consequences of his actions, the abandonment of friends whose political beliefs he once shared and the knowledge that he has, metaphorically speaking, dropped a loaded gun on a playground.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Liebman’s warts-and-all star turn as Oppie is the evening’s standout, a man forced to live the remaining twenty-two years of his life with the consequences of his actions, the abandonment of friends whose political beliefs he once shared and the knowledge that he has, metaphorically speaking, dropped a loaded gun on a playground.

Avery and Kollender are terrific as Oppie’s troubled romantic partners, and so are Pollono’s Charlotte, Wynne’s Jackie, and Pollonno’s daughter Sophie as Little Boy.

As for the men, Brophy in particular ignites the stage as Frank, with Bottitta’s General Groves (and his Einstein), Grant’s Wilson, Jacobson’s Serber, Nelson’s Haakon (and his Colonel Paul Tibetts), Parsons’s Weinberg, Redfield’s Bethe, Selvey’s Lomanitz, Richards’ Feynman, Landon Tavernier’s Peer de Silva, and Via’s Teller each given their own moments to shine brightly on the Electric Lodge stage.

As for the men, Brophy in particular ignites the stage as Frank, with Bottitta’s General Groves (and his Einstein), Grant’s Wilson, Jacobson’s Serber, Nelson’s Haakon (and his Colonel Paul Tibetts), Parsons’s Weinberg, Redfield’s Bethe, Selvey’s Lomanitz, Richards’ Feynman, Landon Tavernier’s Peer de Silva, and Via’s Teller each given their own moments to shine brightly on the Electric Lodge stage.

Completing Oppenheimer’s finely-calibrated chain of commanding performances are Marwa Bernstein’s Ruth Tolman, Daniel Jordan Booth and Jason Chiumento’s Soldiers, Brendan Farrell’s Kenneth Nichols and Richard Harrison, Rori Flynn’s Waitress, Rick Garrison’s Klaus Fuchs, and Daniel Shawn Miller’s Luis Alvarez and Doctor.

Scenic designer Stephanie Kerley Schwartz’s suitably spare set offers the cast ample room to maneuver as Nicholas E. Santiago’s projections give each scene its evocative title (“The General And The Pinko,” “A Town Of Timber Frames,” etc.).

Dianne K. Graebner earns sky-high marks for designing dozens upon dozens of period costumes as does Matt Richter for his especially dramatic lighting and Christopher Mostatiello for his stunning sound design.

Dianne K. Graebner earns sky-high marks for designing dozens upon dozens of period costumes as does Matt Richter for his especially dramatic lighting and Christopher Mostatiello for his stunning sound design.

Bernstein scores too for some sultry vocals and striking choreography, and the same goes for Redfield’s musical direction and tickling of the ivories.

Oppenheimer is produced by John Perrin Flynn. Barbara Kallir and Sam Kofford are assistant directors. Tor Brown is lighting co-designer, Michelle Hanzelova is projection assistant designer, and Jacquelyn Gutierrez is assistant scenic designer.

Oppenheimer is produced by John Perrin Flynn. Barbara Kallir and Sam Kofford are assistant directors. Tor Brown is lighting co-designer, Michelle Hanzelova is projection assistant designer, and Jacquelyn Gutierrez is assistant scenic designer.

Amanda Bierbauer is production manager and David A. Mauer is technical director. Casting is by Victoria Hoffman. Jennifer Sorenson understudies Kitty, Charlotte, and Ruth.

It’s hard to overstate just how much of a feather it is in Rogue Machine’s cap to give Oppenheimer its first American staging since its 2015 Royal Shakespeare Company debut. That this U.S. Premiere represents Los Angeles membership theater at its most vibrant and indispensable gives L.A. audiences even more reason to cheer.

The Electric Lodge, 1416 Electric Ave., Venice.

www.roguemachinetheatre.com

–Steven Stanley

November 25, 2018

Photos: John Perrin Flynn

Tags: J. Robert Oppenheimer, Los Angeles Theater Review, Rogue Machine Theatre, Tom Morton-Smith

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2025 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2025 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY