The wordless five-minute sequence that introduces us, heartstoppingly, to a Tom Wingfield haunted by memories that even years of distance have been unable to extinguish is but the first indication that Christian Lebano’s vision for Tennessee Williams’ most enduring classic is one we have not yet seen, and one that we will be talking and thinking about long after the light dims on the last of Tom’s sister’s precious Glass Menagerie.

Suffice it to say that without altering a word of Williams’ script, all the while respecting the playwright’s deliberately specific stage directions in a way some contemporary directors seem ill-inclined to do, Lebano gives us a Glass Menagerie that engrosses, entertains, and moves us in a way most revivals can only hope for.

Suffice it to say that without altering a word of Williams’ script, all the while respecting the playwright’s deliberately specific stage directions in a way some contemporary directors seem ill-inclined to do, Lebano gives us a Glass Menagerie that engrosses, entertains, and moves us in a way most revivals can only hope for.

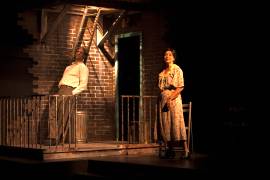

As any theater aficionado can tell you, The Glass Menagerie unfolds in the memory of a man who followed in his father’s footsteps by deserting a stifling family life for one of adventure, and director Lebano deliberately keeps Tom (Christian Durso) outside the action until well into the play’s first scripted scene, the better to remind us that what we are witnessing are events recalled through the faded curtains of Tom’s long-ago memories.

We never learn whether Tom’s dad (“a telephone man who fell in love with long distances”) looked back with regret at the life and family he abandoned.

We never learn whether Tom’s dad (“a telephone man who fell in love with long distances”) looked back with regret at the life and family he abandoned.

What Williams’ play does make clear—and particularly at the Sierra Madre Playhouse—is that Tom’s decision to abandon his mother Amanda (Katherine James) and more especially his sister Laura (Angela Muller) still weighs heavily on his conscience, even years later.

The playwright makes it equally understandable why Tom might have wanted to flee from the drudgery of a day-to-day existence that began each morning with the grating call of “Rise and shine” from his wilted Southern belle of a mother, followed by a tedious factory job which slowly but surely was killing his spirit.

The playwright makes it equally understandable why Tom might have wanted to flee from the drudgery of a day-to-day existence that began each morning with the grating call of “Rise and shine” from his wilted Southern belle of a mother, followed by a tedious factory job which slowly but surely was killing his spirit.

Tom, at least, has the escape that even a drudgery-filled job provides. Painfully shy Laura has no such out, and stigmatized by a limp and incapable of completing even a week of the typing class Amanda still thinks her daughter is attending, she chooses now to spend her days taking solitary walks in the wintry cold.

Only Laura’s “menagerie” of tiny glass animals seems to give her a reason to live, that is until Tom invites fellow factory worker Jim O’Connor (Ross Philips), a former classmate of Laura’s—and the object of her secret affection—to dinner.

With over eight hundred submissions from which to hand-pick his cast, it’s no wonder director Lebano found what can only be described as a dream team, beginning with Durso’s profoundly moving Tom, both the ramshackle wreck of a man he has become and the long-forgotten youthful dreamer now stifled by a go-nowhere life in the midst of the Great Depression.

With over eight hundred submissions from which to hand-pick his cast, it’s no wonder director Lebano found what can only be described as a dream team, beginning with Durso’s profoundly moving Tom, both the ramshackle wreck of a man he has become and the long-forgotten youthful dreamer now stifled by a go-nowhere life in the midst of the Great Depression.

James dazzles as Amanda, capturing her every facet, from her indomitable optimism to her grating querulousness to her still potent charm. And just wait till Philips’ Jim gets Amanda’s juices flowing like they haven’t flowed since that long-ago evening she had a grand total of seventeen gentleman callers, a fact she won’t let anyone forget.

Muller’s exquisite Laura is another performance gem, a young woman whose insecurities have crippled her far more significantly than her faltering walk, that is until her first-ever gentleman caller makes her realize (in a breathtaking Cate Caplin-choreographed Fred-and-Ginger dream) that she is indeed “a pretty girl, Mama.”

Muller’s exquisite Laura is another performance gem, a young woman whose insecurities have crippled her far more significantly than her faltering walk, that is until her first-ever gentleman caller makes her realize (in a breathtaking Cate Caplin-choreographed Fred-and-Ginger dream) that she is indeed “a pretty girl, Mama.”

Last but not least, there is Philips’ cocky yet absolutely sincere charmer of a Jim, a young man who like Amanda must cope with having his better days—his years as a high school star—behind him, though fortunately, hopefully, not irredeemably so.

Aiding enormously in achieving Lebano’s vision is his production design team, most notably composer Jonathan Beard’s stunningly wistful musical underscoring, an integral part of Jeff Gardner’s impeccable sound design, and Erin Walley’s multilayer lace-curtained set, one that frames the action like the photo of that long-gone telephone man still grinning down in black-and-white, just one of Shara Abvabi’s memorable projections.

Aiding enormously in achieving Lebano’s vision is his production design team, most notably composer Jonathan Beard’s stunningly wistful musical underscoring, an integral part of Jeff Gardner’s impeccable sound design, and Erin Walley’s multilayer lace-curtained set, one that frames the action like the photo of that long-gone telephone man still grinning down in black-and-white, just one of Shara Abvabi’s memorable projections.

Pablo Santiago’s evocative lighting design still needed some fine-tuning on opening night, but Thomas Nagata’s 1930s properties (including all those glass figurines), Candice Cain’s pitch-perfect period costumes, Krys Fehervari’s equally fine hair-and-makeup design, and Orlando de la Paz’s scenic painting are all topnotch.

Understudy Jackson Kendall covers the role of Tom.

Alexandra Wright is assistant director. Derek R. Copenhaver is production stage manager and Emily Hopfauf is assistant stage manager and wardrobe mistress. Additional program credits include Diane Siegel (lobby curator and outreach coordinator), Rebecca Hairston (assistant lighting designer), Deborah Ross-Sullivan (dialect coach), Jennifer Gies (production manager), and Todd McCraw (technical director).

The Glass Menagerie is produced by Estelle Campbell and Lebano.

A reimagining that does not seek needlessly to reinvent, Christian Lebano’s vision for Tennessee Williams’ first-and-finest deserves to be seen, both by Glass Menagerie fans and by those who have yet to discover its many rewards.

Sierra Madre Playhouse, 87 W. Sierra Madre Blvd., Sierra Madre.

www.sierramadreplayhouse.org

–Steven Stanley

May 6, 2016

Photos: Gina Long

Tags: Los Angeles Theater Review, Sierra Madre Playhouse, Tennessee Williams

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2026 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2026 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY