RECOMMENDED

The Fountain Theatre follows its multiple award-winning 2012 production of Tarell Alvin McCraney’s In The Red And Brown Water with the Los Angeles Premiere of the 33-year-old playwright’s The Brothers Size, and while the production is as beautifully acted as they get, I am a good deal less enamored with the second in McCraney’s Brother/Sister Plays trilogy than I was with the first.

In The Red And Brown Water, as Fountain Theatre regulars will recall, told the tale of high school track star Oya and her dream to escape the projects of San Pere, Louisiana for the proverbial “better life.” Figuring prominently in Oya’s story was a young man named Ogun, sweet, sincere, and utterly lovestruck with our heroine, and sly, sassy teenaged Elegba, whose sexy six-foot frame belied his nickname “L’il Elegba” (and who appeared to have as much of an eye for the menfolk as for the ladies).

Only Ogun and Elegba are back for The Brothers Size from among In The Red And Brown Water’s large and varied cast of characters, the pair of them quite a few years older and wiser for their life experiences.

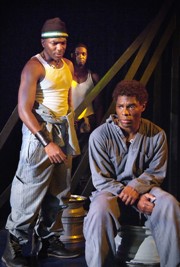

Ogun Size (Gilbert Glenn Brown this time round) now runs a local auto repair shop while younger brother Oshoosi (Matthew Hancock), recently released from “the pen,” lazes around the house despite repeated claims to be searching for work.

Ogun Size (Gilbert Glenn Brown this time round) now runs a local auto repair shop while younger brother Oshoosi (Matthew Hancock), recently released from “the pen,” lazes around the house despite repeated claims to be searching for work.

Unable to tolerate Oshoosi’s lethargy any longer, Ogun puts his younger brother to work (it’s either that or get out), thereby establishing a certain détente between them—that is until who should show up at their doorstep but Oshoosi’s prison cellmate, none other than Elegba himself (Theo Perkins reprising the role he played two years back), whose “eye for the menfolk” may have found expression in his and Oshoosi’s prison cell-for-two.

In The Red And Brown Water benefited considerably from the eclectic bunch of locals that populated Oya’s life—her foxy but sadly short-lived Mama Mojo, man-hunting Louisiana MILF Aunt Elegua, local flirts and gossips Nia and Shun, white shopkeeper O Li Run, and local DJ “The Egungun”—along with so much song and dance that the production seemed at times almost as much a musical as The Color Purple.

By contrast, not all that much “happens” in The Brothers Size, which places considerably more emphasis on McCraney’s dialog, alternately described by devotees as “lyrical” or “poetic,” adjectives which immediately set off a warning alarm in this reviewer’s head. Indeed, my review of In The Red And Brown Water included the caveat that “Playwright McCraney’s blend of poetic speech and street talk didn’t always work for this reviewer, nor did the integration of stage directions into dialog,” though I ended up dismissing these objections as “quibbles” in a production that, as I put it, “any true lover of original, inventive, risk-taking theater will not want to miss.”

By contrast, not all that much “happens” in The Brothers Size, which places considerably more emphasis on McCraney’s dialog, alternately described by devotees as “lyrical” or “poetic,” adjectives which immediately set off a warning alarm in this reviewer’s head. Indeed, my review of In The Red And Brown Water included the caveat that “Playwright McCraney’s blend of poetic speech and street talk didn’t always work for this reviewer, nor did the integration of stage directions into dialog,” though I ended up dismissing these objections as “quibbles” in a production that, as I put it, “any true lover of original, inventive, risk-taking theater will not want to miss.”

Without In The Red And Brown Water’s multiple plusses, I find it harder to dismiss those objections this time round, especially when McCraney’s characters launch into lengthy flashback monologs à la Greek Tragedy, hardly my favorite theatrical genre.

Fortunately, The Brothers Size has enough going for it to merit recommending, even to those with tastes similar to my own.

First and foremost amongst its assets are its stars, all three of them doing dazzling work, from Brown’s forceful, grounded Ogun to Hancock’s intense, appealing Oshoosi, to Perkins’ sly, sexy Elegba. Actors don’t get any better, or more powerful, or more polished than these, especially with a director as gifted as Shirley Jo Finney (back from In The Red And Brown Water) to guide them.

First and foremost amongst its assets are its stars, all three of them doing dazzling work, from Brown’s forceful, grounded Ogun to Hancock’s intense, appealing Oshoosi, to Perkins’ sly, sexy Elegba. Actors don’t get any better, or more powerful, or more polished than these, especially with a director as gifted as Shirley Jo Finney (back from In The Red And Brown Water) to guide them.

Add to that fellow returnee Ameenah Kaplan’s electric choreography (I have the sense that the Fountain production might feature more dance than others before it) and Peter Bayne’s stunning original music and sound design and you’ve got a production that offers a good deal more onstage than on the printed page.

Scenic designer Hana S. Kim’s darkly-hued set may at first glance appear nearly bare, but it is clearly the work of a talented designer as is Pablo Santiago’s dramatic if murky lighting. Still, dusky tones and dim lighting can prove soporific when The Brothers Size launch into those flashback soliloquies.

Costume designer Naila Aladdin Sanders does her accustomed excellent work, though Brother/Sister Play #1 gave her considerably more opportunity to strut her imaginative stuff than #2 does. Misty Carlisle’s multiple props (lots of wheels and hubcap paraphernalia) are winning creations. Kudos go too to Brenda Lee Eager’s gorgeous vocal arrangements and to the three stars’ exquisite harmonizing. JB Blanc’s dialect coaching gets thumbs up as well.

Costume designer Naila Aladdin Sanders does her accustomed excellent work, though Brother/Sister Play #1 gave her considerably more opportunity to strut her imaginative stuff than #2 does. Misty Carlisle’s multiple props (lots of wheels and hubcap paraphernalia) are winning creations. Kudos go too to Brenda Lee Eager’s gorgeous vocal arrangements and to the three stars’ exquisite harmonizing. JB Blanc’s dialect coaching gets thumbs up as well.

Terri Roberts is production stage manager and Shawna Voragen assistant stage manager.

Ultimately, whether you love The Brothers Size to bits or merely admire its many strong points will depend on your affinity for McCraney’s unique writing style. Though the playwright’s much lauded lyricism is not this reviewer’s cup of tea, the Fountain’s latest merits those of a similar bent to mine giving it a look-see.

The Fountain Theatre, 5060 Fountain Ave., Los Angeles.

www.FountainTheatre.com

–Steven Stanley

June 19, 2014

Photos: Ed Krieger

Tags: Fountain Theatre, Los Angeles Theatre Review, Tarell Alvin McCraney, The Brother/Sister Plays

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2026 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2026 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY