Sarah Ruhl examines how a centuries-old theatrical tradition and the folks who take part in the spectacle year after year are affected by the epoch in which they create this annual event in Passion Play, and before you jump to the conclusion that such heavy subject matter might prove too weighty to be entertaining, remember that it’s Tony-nominated Ruhl we’re talking about.

In other words, despite Passion Play’s potentially ponderous nature (and its nearly three-hour running time), the playwright who gave us The Clean House, Eurydice, and—most famously—In the Next Room (or The Vibrator Play), ensures that her 2005 dramedy has more than its fair share of whimsy, quirkiness, and lyrical charm.

In other words, despite Passion Play’s potentially ponderous nature (and its nearly three-hour running time), the playwright who gave us The Clean House, Eurydice, and—most famously—In the Next Room (or The Vibrator Play), ensures that her 2005 dramedy has more than its fair share of whimsy, quirkiness, and lyrical charm.

Divided into three acts, with a “fake” intermission between Acts One and Two and an honest-to-goodness lobby break before Act Three, Ruhl’s Passion Play unfolds first in Elizabethan England, then in 1934 Nazi Germany, and finally in mid-to-late 20th Century South Dakota, a major political leader from each era taking advantage of this dramatic reenactment of Christ’s trial, suffering and death to suit his or her own purposes.

To Queen Elizabeth, the Passion Play must be shut down as part of her efforts to banish Roman Catholicism from the land. To Adolph Hitler, the Passion Play’s most controversial aspect, its damnation of the Jews as Christ Killers, serves his political agenda to malevolent perfection. To President Ronald Reagan, a Midwestern staging of the Passion Play symbolizes his administration’s emphasis on good old-fashioned “family values.”

To Queen Elizabeth, the Passion Play must be shut down as part of her efforts to banish Roman Catholicism from the land. To Adolph Hitler, the Passion Play’s most controversial aspect, its damnation of the Jews as Christ Killers, serves his political agenda to malevolent perfection. To President Ronald Reagan, a Midwestern staging of the Passion Play symbolizes his administration’s emphasis on good old-fashioned “family values.”

That playwright Ruhl has a single actor (Shannon Holt at the Odyssey) bring to gender-bending life all three of these historical figures is but one aspect of Passion Play’s unique fascination.

All three eras feature the same cast of actors, some of them playing three separate incarnations of the same character while others play a trio of very different characters serving similar dramatic functions.

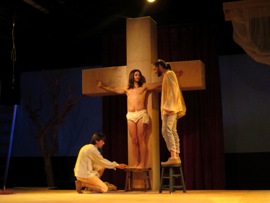

Daniel Bess’s John, Eric, and J are all the Passion Play’s Jesus, the first a sweet, rather asexual fisherman, the second sharing a passionate same-sex kiss, the third a decidedly hetero soap opera heartthrob. Likewise, all three characters brought to life by Christian Leffler portray the Passion Play’s Pontius Pilate, the third of them the evening’s most dramatic and powerfully rendered, a Vietnam vet unable to shake the post traumatic stress disorder brought upon by the horrors of war.

Daniel Bess’s John, Eric, and J are all the Passion Play’s Jesus, the first a sweet, rather asexual fisherman, the second sharing a passionate same-sex kiss, the third a decidedly hetero soap opera heartthrob. Likewise, all three characters brought to life by Christian Leffler portray the Passion Play’s Pontius Pilate, the third of them the evening’s most dramatic and powerfully rendered, a Vietnam vet unable to shake the post traumatic stress disorder brought upon by the horrors of war.

Dorie Barton’s Mary I (the Virgin) and Amanda Troop’s Mary 2 (the Magdalene) are likewise given strikingly different variations on the same character in each act. Barton’s lusty Elizabethan wench bears only superficial resemblance to the glamorous German actress of Act Two and Act Three’s Midwestern wife torn between two brothers. Troop gets to play Mary Magdalene’s interpreter as a young woman confused by her same-sex longings, the daughter of the elderly man whose traditional role as Christ has been taken over by his son, and a folksy, salt-of-the earth toll booth worker in Act Three.

Dorie Barton’s Mary I (the Virgin) and Amanda Troop’s Mary 2 (the Magdalene) are likewise given strikingly different variations on the same character in each act. Barton’s lusty Elizabethan wench bears only superficial resemblance to the glamorous German actress of Act Two and Act Three’s Midwestern wife torn between two brothers. Troop gets to play Mary Magdalene’s interpreter as a young woman confused by her same-sex longings, the daughter of the elderly man whose traditional role as Christ has been taken over by his son, and a folksy, salt-of-the earth toll booth worker in Act Three.

Also figuring prominently in the action are Tobias Baker and John Charles Meyer as a pair of carpenters charged with nailing Christ to the cross and John Proska as the director of all three eras’ Passion Play.

Bill Brochtrup brings to life a trio of outsiders—a visiting Friar, a visiting Englishman, and a VA psychiatrist; Dylan Kenin gets to play a machinist, a rather frightening German Officer, and an almost equally frightening young stage director; and Brittany Slattery is given the plum assignment of Act One and Two’s Village Idiot, rendered notably Jewish in Nazi Germany, and the child-turned-adolescent who may be the daughter of one man or perhaps his brother’s. Jason Liska and Beth Mack complete the ensemble in assorted cameos.

With director Bart DeLorenzo bringing the same inspired touch to Passion Play that he’s brought to productions at A Noise Within, South Coast Rep, the Geffen, and his own Evidence Room, Passion Play’s two hours and fifty minutes go by surprisingly lickety-split, aided and abetted by a couldn’t-be-better cast, with Leffler’s Act Three PTSD-afflicted vet and Holt’s magnificent trio of world leaders the evening’s biggest, but far from only standout performances. (The evening’s pre-show meet-and-greet is a delightful DeLorenzo touch.)

With director Bart DeLorenzo bringing the same inspired touch to Passion Play that he’s brought to productions at A Noise Within, South Coast Rep, the Geffen, and his own Evidence Room, Passion Play’s two hours and fifty minutes go by surprisingly lickety-split, aided and abetted by a couldn’t-be-better cast, with Leffler’s Act Three PTSD-afflicted vet and Holt’s magnificent trio of world leaders the evening’s biggest, but far from only standout performances. (The evening’s pre-show meet-and-greet is a delightful DeLorenzo touch.)

Not surprisingly, costume designer Raquel Barreto gets the production’s most exciting design challenge, one she and her assistant Rachel Clinkscales pass with flying colors and three epochs’ worth of period outfits. John Ballinger earns top marks for his striking, mood-enhancing sound design, a combination of effects and his own original music, distinctive for each historical period. Lighting designer Michael Gend gets to dazzle as well, particularly when the Village Idiot’s magic apparently turns the sky red, all of this unfolding on scenic designer Frederica Nascimento’s imaginative, expansive set.

Passion Play is produced by Beth Hogan and DeLorenzo. Carol Solis is stage manager and Joe Behm production manager.

As might be expected given playwright and subject matter, Passion Play is more than a little bit “all over the place” thematically and stylistically, something that will excite certain audience members and leave others scratching their heads.

As might be expected given playwright and subject matter, Passion Play is more than a little bit “all over the place” thematically and stylistically, something that will excite certain audience members and leave others scratching their heads.

Regardless of which camp you find yourself in, Sarah Ruhl’s Passion Play is exciting, challenging theater, and quite marvelously performed and staged at the Odyssey.

Odyssey Theatre Ensemble, 2055 South Sepulveda Boulevard, Los Angeles.

www.odysseytheatre.com

–Steven Stanley

February 13, 2014

Photos: Enci and Michael Gend

Tags: Evidence Room, Los Angeles Theater Review, Odyssey Theatre, Passion Play, Sarah Ruhl

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2026 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2026 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY