Larry Kramer’s landmark drama The Normal Heart gets its first L.A. staging in nearly two decades, and tough as it may be to revisit the earliest days of the AIDS epidemic, this absolutely brilliant production is one that no Los Angeles theater lover should miss, and the younger the audience the better.

The lion that is Larry Kramer still roars loud and furious—and righteously, rightfully so—just as his alter ego Ned Weeks rages against the monster that has only just begun, in the early 1980s, to kill off one friend after another, denouncing too the New York establishment that refuses to acknowledge the epidemic status of this 20th Century plague even as the number of gay men it kills continues to double every six months.

It’s in July of 1981, the same month that the New York Times buried its now prophetic headline RARE CANCER SEEN IN 41 HOMOSEXUALS on page twenty-eight, that we first meet Ned (Tim Cummings) in the waiting room of Dr. Emma Brookner (Lisa Pelikan), a Manhattan physician who has just seen her twenty-eighth case, sixteen of whom have died. Though Emma can’t find anything wrong with Ned—or at least not so far—she informs him that of the two young patients she has just diagnosed, one of them will be dead within a year, maybe both.

It’s in July of 1981, the same month that the New York Times buried its now prophetic headline RARE CANCER SEEN IN 41 HOMOSEXUALS on page twenty-eight, that we first meet Ned (Tim Cummings) in the waiting room of Dr. Emma Brookner (Lisa Pelikan), a Manhattan physician who has just seen her twenty-eighth case, sixteen of whom have died. Though Emma can’t find anything wrong with Ned—or at least not so far—she informs him that of the two young patients she has just diagnosed, one of them will be dead within a year, maybe both.

Having heard that Ned is “well known in the gay world and not afraid to say what you think,” Emma wonders aloud if he might just be the man to get the higher-ups to begin taking action, to which Ned responds that Emma is talking to the wrong person. “What I think is politically incorrect,” he tells her, and diametrically opposed to the prevailing wisdom that “Gay is good, no matter what.”

Still, if anyone can get gay men to “stop having sex,”—yes, Emma’s words are as brief and unequivocal as that—Ned Weeks may be just that man. And for those who might find the good doctor’s advice extreme, she has this simple response: “If having sex can kill you, doesn’t anybody with half a brain stop fucking?”

Ned’s initial attempts to get someone, anyone, to listen are ill-fated. Closeted New York Times reporter Felix Turner (Bill Brochtrup) may write about gay designers and gay discos and gay chefs and gay rock stars (without calling them gay), but he’s not going to be the one to write the first piece about something that’s not part of his job description.

Ned’s wealthy (and straight) older brother Ben (Matt Gottlieb) may have enough bucks to build a brand new million-dollar house (that’s a whopping five million of today’s dollars), and his firm may support multiple charities and other worthy causes, but, he insists, “it’s not up to me to select just what those worthy causes might be.”

Ned’s wealthy (and straight) older brother Ben (Matt Gottlieb) may have enough bucks to build a brand new million-dollar house (that’s a whopping five million of today’s dollars), and his firm may support multiple charities and other worthy causes, but, he insists, “it’s not up to me to select just what those worthy causes might be.”

And so Ned and a small group of concerned gay men—among them Mickey Marcus (Fred Koehler), Bruce Niles (Stephen O’Mahoney), and Tommy Boatright (understudy Ray Paolantonio)—set up their own organization (one based on Gay Men’s Health Crisis, though it is never named), an association fraught with dissension from the get-go. Mickey, once one of the drag queens who fought the cops at Stonewall, feels he has nothing in common with “Brooks Brothers guys” like Bruce, who’s so closeted that he refuses to allow mailings to go out with the word “gay” on the envelope, while “Southern belle” Tommy worries that the organization will only attract “white bread and middle class.”

About the only bright spot in Ned’s life turns out, rather unexpectedly, to be his burgeoning relationship with Felix, a romance whose timing could hardly be any better for two men so desperately in need of love … or worse, given the likelihood that one or the other or both could be the next to exhibit telltale symptoms of a nameless killer without known cause, proven treatment, or hope of a cure.

About the only bright spot in Ned’s life turns out, rather unexpectedly, to be his burgeoning relationship with Felix, a romance whose timing could hardly be any better for two men so desperately in need of love … or worse, given the likelihood that one or the other or both could be the next to exhibit telltale symptoms of a nameless killer without known cause, proven treatment, or hope of a cure.

Nearly thirty years have passed since New York audiences first experienced The Normal Heart, three decades during which Kramer’s masterpiece has become a 1980s period piece without losing an iota of its power, since as Kramer himself put it in an open letter to those attending the play’s 2011 Broadway revival, “AIDS is a worldwide plague. There is no cure. The world has suffered at the very least 75 million infections and 35 million deaths.”

At the time of The Normal Heart’s opening scene, there were 41.

And despite continued resistance by those who condemn anything they dub “sex-negative,” ideas espoused by Kramer back in the ‘80s remain just as powerful and relevant in 2013. Take these quotes from The Normal Heart: “I am sick of guys moaning that giving up careless sex until this blows over is worse than death.” “All we’ve created is generations of guys who can’t deal with each other as anything but erections.” “More sex isn’t more liberating. And having so much sex makes finding love impossible.” “Men do not just naturally not love—they learn not to.” And most prophetic of all way back in 1985: “Why didn’t you guys fight for the right to get married instead of the right to legitimize promiscuity? Maybe if they’d let us get married to begin with none of this would have happened at all.”

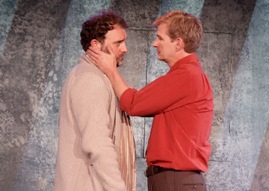

The Normal Heart retains every bit of its power, and not simply as a David-vs.-Goliath tale. (At the time of its Broadway debut, New York Mayor Ed Koch had allocated a paltry $75,000 for public education and community services compared to San Francisco Mayor Dianne Feinstein’s $16,000,000.) It is also the story of men of valor, tenacity, and grace in the face of Evil with a capital E. And it is a love story of the first magnitude, particularly as brought to heart-warming, heart-wrenching life by Cummings and Brochtrup, L.A. treasures who have quite simply never been better.

I wish Larry Kramer could see Tim Cummings’ stunning tour-de-force as Ned, every bit as prickly and off-putting as Kramer himself could/can be, and every bit as human and worthy of love and respect and admiration. Cummings gives a performance of epic proportions, as colorful and multilayered and unfettered as they get, one that leaves both actor and audience drained and dazzled.

I wish Larry Kramer could see Tim Cummings’ stunning tour-de-force as Ned, every bit as prickly and off-putting as Kramer himself could/can be, and every bit as human and worthy of love and respect and admiration. Cummings gives a performance of epic proportions, as colorful and multilayered and unfettered as they get, one that leaves both actor and audience drained and dazzled.

There’s not a major supporting character that Kramer doesn’t give his own bravura scene or scenes, and man oh man does this cast of L.A.-based actors deliver.

NYPD Blue’s Brochtrup may seem relegated to romantic charmer in Act One, but as Felix faces his own mortality, the actor (openly gay way back when there were few with the guts to say so publicly) rises to the occasion in scenes so exquisitely played they will break your heart.

The same can be said for Kohler’s Mickey, brought to the point of near suicide by the realization that after fifteen years of “fighting for our right to be free and make love whenever, wherever,” he is now being considered in some circles to be a murderer; O’Mahoney’s Bruce, a man of ice and steel brought to his knees by an unendurable (and to Ned entirely unexpected) loss; Paolantonio, so pitch-perfect as a gay male Scarlet O’Hara that you’d swear he’d been rehearsing all along with the rest of the cast instead of merely watching and waiting to jump off the high-diving board; Gottlieb’s Ben, unflinching as a brother who loves without respect … until Ned’s unconditional love for Felix opens his eyes and frees his heart; and Pelikan, never more superb than she is here as a woman whose bout with childhood polio made her the fiercest champion the gay community could ever have asked for.

The same can be said for Kohler’s Mickey, brought to the point of near suicide by the realization that after fifteen years of “fighting for our right to be free and make love whenever, wherever,” he is now being considered in some circles to be a murderer; O’Mahoney’s Bruce, a man of ice and steel brought to his knees by an unendurable (and to Ned entirely unexpected) loss; Paolantonio, so pitch-perfect as a gay male Scarlet O’Hara that you’d swear he’d been rehearsing all along with the rest of the cast instead of merely watching and waiting to jump off the high-diving board; Gottlieb’s Ben, unflinching as a brother who loves without respect … until Ned’s unconditional love for Felix opens his eyes and frees his heart; and Pelikan, never more superb than she is here as a woman whose bout with childhood polio made her the fiercest champion the gay community could ever have asked for.

Dan Shaked (as Craig Donner and Grady) and Jeff Witzke (as David, Hiram, and Examining Doctor) have less to do in their multiple roles, but each contributes invaluably to the ensemble.

Simon Levy, at the peak of his talents, directs scene after gut-punching scene, aided by scenic designer Jeff McLaughlin’s abstract but infinitely mutable set, sound designer Peter Bayne’s suspenseful, pulsating original music score, and R. Christopher Stokes’ intensely dramatic lighting design. Naila Aladdin-Sanders’ costumes evoke the early 1980s to perfection as do Misty Carlisle’s multiple props, from medical gear to leaflets to corded phones. Perhaps most effective of all is Adam Flemming’s stage-wide video design, artfully projecting images of the era (famous faces, newspaper headlines, lists of names of the dead), along with the month, the year, and the rapidly rising death count.

Corey Womack is production stage manager, Terri Roberts associate producer/assistant stage manager, and Scott Tuomey technical director. The Normal Heart is produced by Deborah Lawlor and Stephen Sachs. Casting is by Raul Staggs.

The Normal Heart’s 2011 Broadway’s revival earned a Best Revival Tony along with raves for its star-studded cast, one which included Tony-winning turns by Ellen Barkin as Emma and John Benjamin Hickey as Felix. The Fountain Theatre cast may not be as nationally known “names,” but they prove every bit as deserving of accolades and awards.

The Normal Heart’s 2011 Broadway’s revival earned a Best Revival Tony along with raves for its star-studded cast, one which included Tony-winning turns by Ellen Barkin as Emma and John Benjamin Hickey as Felix. The Fountain Theatre cast may not be as nationally known “names,” but they prove every bit as deserving of accolades and awards.

Older theatergoers will likely flock to The Normal Heart both for its reputation and as a way to recall, for better or worse, a time lived through and survived. The production’s challenge, and one I hope the Fountain will meet, will be to get younger bodies into seats. For anyone under thirty, the term “must-see” is putting it mildly.

The Fountain Theatre, 5060 Fountain Ave., Los Angeles.

www.FountainTheatre.com

–Steven Stanley

October 3, 2013

Photos: Ed Krieger

Tags: AIDS Epidemic, Fountain Theatre, Larry Kramer, Los Angeles Theater Review, The Normal Heart

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2026 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2026 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY