Racism in the early 20th Century South may seem an unlikely subject for a Broadway musical—let alone two—yet wonder of wonders, just as Jason Robert Brown and Alfred Uhry’s Parade draws to a close at San Diego’s Cygnet Theatre comes the West Coast Premiere of John Kander and Fred Ebb’s The Scottsboro Boys at the Old Globe, and as was the case with its predecessor, this is indeed cause for celebration.

Both of these fact-based musicals center on murder trials fueled by bigotry and lies. Parade’s unjustly accused hero, Leo Frank, ended up lynched, largely because of anti-Semitism down south in Georgia. The nine Scottsboro Boys fared a tad better in Tennessee, though only relatively so.

In each case, the darkness of injustice has given birth to an extraordinary musical.

Parade tells its story more or less literally (though director Sean Murray gave it a surreal spin at Cygnet). The Scottsboro Boys takes a far more daring approach—staging the early 1930s arrest and trials of nine African-American teenagers accused of rape … as an old-fashioned minstrel show, one in which all roles but two are played by African-American males, and this includes the two white female accusers, Northern lawyer Sam Liebowitz, and assorted Caucasian officers of the law. Our host, The Interlocutor, is The Scottsboro Boys’ lone white performer, and an African-American actress dressed in a 1950s shirtwaist observes the proceedings throughout—for reasons we will come to understand in the show’s inspiring final moments.

The juxtaposition of one of the darkest chapters in 20th Century American history with a theatrical genre now considered racist is risky business indeed, and some have taken issue with any resurrection of the long-dead minstrel show format for 21st Century entertainment purposes.

This reviewer feels otherwise.

First and foremost, there is Kander & Ebb’s music, a dozen and a half new songs from the creators of Cabaret, Chicago, and Kiss Of The Spider Woman. Though hints of past Kander melodies and rhythms are heard in rousing anthems like “Shout!,” “That’s Not The Way We Do Things,” “Never Too Late,” and the title song, the addition of the minstrel show motif makes them sound thrillingly fresh and new. As for slower-tempo numbers, a memorable pair of them (“Go Back Home” and “You Can’t Do Me”) are among Kander & Ebb’s best.

Then there’s David Thompson’s book, which satirizes offensive racial stereotypes while maintaining the minstrel show’s bona fide entertainment value. Yes, it may seem odd to tell a story as grim as that of The Scottsboro Boys through the medium of minstrel, but Thompson’s book never lets us forget the facts, and while bouncy musical numbers may seem an odd way of presenting a) racist testimony, b) a horrendously unjust series of verdicts, and c) the ultimate fates of those nine innocent youths, it’s hard to imagine a more literal approach not being a downer from start to finish—something which The Scottsboro Boys most definitely is not.

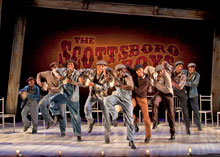

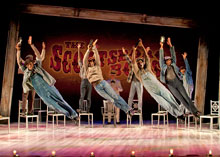

None of this would matter, of course, without a cast as phenomenal as the performers assembled at the Old Globe and the brilliant contributions of powerhouse director-choreographer Susan Stroman.

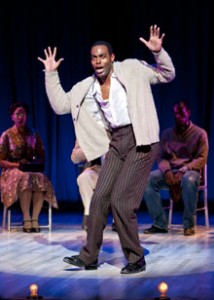

David Bazemore, Shavey Brown, Nile Bullock, Christopher James Culberson, Clifton Duncan, Eric Jackson, James T. Lane, Clifton Oliver, and Clinton Roane are The Scottsboro Boys, and another nine more gifted triple threats you are unlikely to find on any stage other than the Old Globe’s any time soon, with special mention due Duncan’s powerful turn as the heroic Haywood Patterson, the role which scored its originator, Joshua Henry, one of the show’s twelve Tony nominations.

Two more Tony nominations went to the actors originating the roles of Mr. Bones and Mr. Tambo, the minstrel stars whose lighter complexions allow them to play the show’s assorted Caucasian characters, roles performed here with sly panache by the fabulous duo of Jared Joseph and JC Montgomery.

Ron Holgate’s deliciously, deliberatly creepy Interlocutor and C. Kelly Wright’s silent but powerful Lady are other Scottsboro Boys standouts.

Kander & Ebb, Stroman, and cast take what might otherwise be unbearably gloomy material and make it magically entertaining, all the while never losing track of the seriousness of the crimes committed against The Boys. When, in “Alabama Ladies,” their white accusers sing, “another Negro grabbed me by the boobies. Oh it scared me half to death,” we chuckle at the sight of Lane and Oliver in female semi-drag, cringe at the use of “Negro,” and are made painfully aware that the charge of raping a white woman meant the death penalty in the 1930s South, no two ways about it. Yankee lawyer Liebowitz’s “That’s Not The Way We Do Things” is ostensibly about how much better things are up North than in Tennessee, but lyrics like “just ask my maid, Magnolia, and I’m sure she’d agree” indicate that African-American New Yorkers still had to live their lives under the thumb of a dominant white society. And the Attorney General’s “Financial Advice” to Ruby to “go get you some Jew money” suggests that anti-Semitism remained as virulent as it was twenty years earlier when Parade’s Leo Frank was lynched.

Still, when music director/conductor Eric Ebbenga and the production’s nine-piece orchestra start playing and the cast start singing … and dancing to Stroman’s thrilling choreography, The Scottsboro Boys is as exciting as musical theater can get.

Scenic designer Beowulf Boritt does as much with a bunch of straight-back chairs and some planks and tambourines as he’s done before with other far more literal sets. Ken Billington lights Boritt’s set vividly and with seemingly limitless variety. Toni-Leslie James’ costumes are a wonder, and Jon Weston’s sound design, Larry Hochman’s orchestrations, Glen Kelly’s musical arrangements, David Loud’s vocal arrangements, and Rick Sordelet’s fights deserve highest marks as well.

Associate director and choreographer Jeff Whiting’s contributions merit nearly as large a font in the program as Stroman’s. Eric Santagata is assistant choreographer and Joshua Halperin stage manager.

The Scottsboro Boys lost all twelve of its Tonys to The Book Of Mormon and lasted barely more than two months on Broadway, and given its subject matter and unorthodox storytelling technique, it’s not hard to see why. That shows like its fellow Tony competitors The Book Of Mormon and Sister Act would end up with a far broader appeal could probably have been foretold from the get-go.

Still, despite not being destined to hit it big on Broadway, The Scottsboro Boys should do quite well indeed in regional theaters like the Old Globe, where season subscriptions, more affordable ticket prices, and different audiences expectations are likely to give it a rich future life. Those Scottsboro Boys are not about to be consigned to the musical theater history books. Not by a long shot.

Old Globe Theatre, Balboa Park, San Diego.

www.oldglobe.org

–Steven Stanley

May 6, 2012

Photos: Henry DiRocco

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2025 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2025 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY