In the decade since David Auburn’s Proof premiered on Broadway, the four-character drama has become one of the most produced plays in the United States. For a time there, it seemed that just about every regional, intimate, or community theater in Los Angeles was doing, had done, or was going to do their own version of the Broadway hit—and no wonder. How many plays can you name that have won the Drama Desk Award for Best New Play, the Lucille Lortel Award for Outstanding Play, the New York Drama Critics’ Circle and Tony Awards for Best Play, and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama? Add to that the fact that it’s a one-set play which offers several of the best acting roles of this or any decade, and you’ve got a play that any theater in its right mind would want to have as part of its season.

It’s been a while, though, since Angelinos have had the chance to savor Auburn’s absorbing, thought-provoking, deeply satisfying family drama, thus its midweek revival at Open Fist Theatre comes as welcome news for Proof-lovers like this reviewer, particularly since this co-production with The Aquila/Morong Studio is about as close to perfect a Proof as can be imagined.

A drama about a world-renowned mathematician and his aspiring mathematician daughter might not seem ripe for theatrical magic, at least not on the surface, but playwright Auburn’s mix of math and madness is a heady one.

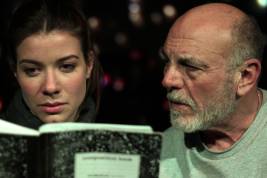

We first meet college professor/mathematical genius Robert (Carmen Argenziano) and his gifted daughter Catherine (Tessa Ferrer) on Catherine’s 25th birthday, Dad having picked up a bottle of champagne to celebrate the event. Before long, conversation has turned to Robert’s long history of mental illness and Catherine’s fear that she may have inherited more than just a mathematical mind from her father—a fear quickly understood when Robert lets slip a bombshell (at least for us in the audience). He has been dead for a week, his burial is tomorrow, and Catherine is for all we know every bit as loony as dear deceased Dad.

Meanwhile in another part of the three-bedroom house, Robert’s former student Hal (Matt Marquez) is (with Catherine’s permission) busily going through his professor’s notebooks in hopes of finding out if perhaps, during a period of remission, Robert wrote down another of those brilliant proofs he had come up with so often as a young man. So far, however, Hal has unearthed nothing, and Catherine begins to suspect that the reason for his search may be less altruistic than Hal claims. Might he not be looking for a proof to pass off as his own and thereby insure himself a lucrative future in his chosen field?

Just as Hal is about to leave for the evening, Catherine discovers one of her father’s notebooks hidden inside his jacket and is, quite naturally, outraged … or at least she is until Hal persuades her of the purity of his intentions. It helps too that Hal is darned cute for a math geek, a rock musician to boot, and someone who’s had a thing for Catherine for at least four years now.

Though Hal provides Catherine with at least one good reason to hope for a bright few months ahead, her older sister Claire (Nicole Stuart) is another matter. The successful New York financial analyst may have ended up with only “one one-thousandth” of her father’s prodigious ability with numbers, but she’s also avoided inheriting any tendency towards mental instability. Claire has arrived back at the family homestead with two thoughts in mind: to sell her father’s house as quickly as possible, and to convince Catherine to move to the Big Apple where younger sister can live close by older sis and get the psychiatric help she apparently needs.

As might be expected, Catherine takes to neither of her sister’s plans, especially when a romantic turn of events with Hal gives her even more reason to want to stay put in Chicago. Newly confident about herself and Hal’s feelings for her, Catherine presents him with the key to a locked drawer in her father’s desk. There, the math geek makes what might well be an earth-shattering discovery, the revelation of which is followed by an end-of-act bombshell that gives audience members ample food for intermission talk.

In titling his play Proof, writer Auburn has more in mind than simply the mathematical proofs Robert made his life’s work. At its heart, Proof is the story of a young woman’s quest to prove her sanity and her genius, both to herself and to the outside world, no easy task considering her legacy as well as the doubts her sister and Hal have cast over the claim that is central to Proof’s gripping second act.

Not surprisingly, the role of Catherine turns out to be one of best of recent years for a 20something actress, with Mary Louise Parker winning the 2001 Tony Award as Best Actress in Proof’s original Broadway run. Following in her footsteps, Open Fist’s Ferrer makes a truly memorable Los Angeles theater debut, one which has doubtless contributed to the show’s current extension. Ferrer is that rare actress capable of revealing as much of what’s happening inside her head as out, and much of the pleasure of watching her performance is in observing her reactions to what others say and do, because what we are seeing are not the thought processes of an actor but those of the character she is inhabiting. Ferrer makes us believe both in Catherine’s intelligence and in her fear of insanity, and she keeps us rooting for her character even as we wonder if Claire might just be right.

It’s hard to imagine a better Hal, or an actor more right for the role than Marquez, with his curly black mop of hair, rosy cheeks, boy-next-door sweetness, and nerdy sex appeal, but his terrific performance is about much more than just intelligent good looks and charm. Like Ferrer, there is an immediacy in Marquez’s work that makes it absolutely real, a spontaneity that can be honed in an acting class but is ultimately the gift of a truly natural talent.

Argenziano is downright brilliant as Robert, giving us three distinctly different characterizations per Auburn’s script—the idealized father of Catherine’s imagination, the imperfect one he was in reality, and the mad man he ultimately became. Argenziano’s final scene, as he attempts to persuade Catherine of his genius and ends up revealing his insanity, is truly tour de force work.

As Claire, Stuart does effective work in a tough role that is also the play’s least subtly drawn, that an older sister who is so “by the rules” that most of her time is spent trying to get things right—or at least what she feels would be right.

Director John Hindman deserves highest marks here, and not merely for the performances he has elicited from his actors. The production’s opening sequence, a montage of projected images from Catherine’s childhood (Ferrer’s actual photos and home movies) which starts out a small square on an upstage wall and gradually expands to fill the entire stage as the slide show picks up speed to a breakneck pace, sound designer Peter Carlstedt’s background music providing an absolutely perfect accompaniment. Then lights come up, not on the back porch and yard of math professor Robert’s house where Auburn has situated all of the play’s scenes but inside the home’s cluttered living room/dining area, a choice imposed by the hotel room set Victoria Proffitt has created for Open Fist’s concurrently running main production of Room Service, but one which Hindman has made work, and brilliantly so.

Scenic designer James Spencer has taken the shell of the Room Service set and filled it with the accumulation of decades of living and little attempt at spring cleaning. Necessity proving the mother of invention, situating Proof inside Robert’s house adds rich textures to Auburn’s script, and for the one scene that must take place outside on a freezing night, Hindman simply places a bench downstage below the raised stage, lighting designer Jason Mullen projecting a multitude of stars around it. If only for this entirely new set design, this Proof deserves to be seen…though clearly there are many other reasons to do so.

Proof is produced by Thrill Ride Productions. Caitlin R. Campbell is producer, Alyssa Escalante stage manager, Tommy Burruss technical director, and Alvin Ceballos production manager.

With only one (mid)week of performances remaining in Proof’s six-performance extension, theater lovers (and Proof lovers in particular) are advised not to make the mistake of missing out on this truly unique vision of David Auburn’s multi-award winner. Trust me. This Proof proves to be in a class very much of its own.

Open Fist Theatre, 6209 Santa Monica Blvd., Hollywood.

www.openfist.org

www.aquilamorongstudio.com

–Steven Stanley

March 16, 2011

Photos: Tom Burress

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY