The Tennessee Williams estate is very particular about whom it grants right to Mr. Williams’ plays. Justly concerned about protecting the two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright’s reputation, the estate won’t let just any theater company stage the Williams oeuvre, particularly the two plays which won him the Pulitzer—A Streetcar Named Desire and Cat On A Hot Tin Roof. Other than A Noise Within’s 2000 production and the Geffen’s in 2005, I can’t recall a local staging of Cat, nor can I recall its being produced by a 99-seat theater. Thus, The Neighborhood Playhouse’s just-opened revival of the 1955 classic is a major Southland theatrical event.

The reasons for the Williams estate’s confidence in the Neighborhood Playhouse should be amply clear to those who saw their recent productions of Parade and Our Leading Lady. The Neighborhood Playhouse is a class act in every respect, and director Brady Schwind’s superb staging of Cat On A Hot Tin Roof is no exception. In every respect—performance, direction, and design, this is an all-around Grade A production.

But first a word about the play itself. Taking place in real time, Cat On A Hot Tin Roof unfolds over the course of a single evening at the Mississippi plantation home of multi-millionaire tycoon “Big Daddy” Pollitt. Big Daddy has recently undergone a battery of tests to determine the nature of the abdominal pains he’s been suffering. To his great relief, the doctors have informed and him and his wife “Big Mama” that the only thing wrong with Big Daddy is a spastic colon. In fact, the patriarch is suffering from inoperable, incurable cancer, and is unlikely to live much longer. A contemporary doctor would likely have told Big Daddy the truth about his condition, but this was the mid-1950s and doctors of the time often hid painful truths from their patients, the better to give them “hope” for the future. Big Daddy’s family has gathered together this evening to celebrate his birthday and later, when the time is right, to break the news of Big Daddy’s actual condition to Big Mama.

Big Daddy’s two sons are there, of course. There’s older son (and successful businessman) Gooper, married to Mae, with a gaggle of bratty children in tow and another on the way. There’s also younger son Brick, a sportscaster unable to forget his past glories as a high school football star, or (more significantly) his deceased best friend Skipper. Brick, too, is married (to Maggie, the titular cat), but they are childless, Maggie is frustrated (in more ways than one), and Brick spends all day imbibing drink after drink until he feels that “click” that will make being alive bearable.

Those whose only familiarity with Cat On A Hot Tin Roof is the 1958 film version, shot at the height of the MPAA Production Code, will be surprised at how truly adult Williams’ original script is. If Brick hasn’t been showing Maggie a good time in bed recently, the most likely cause would seem to be a still-repressed sexual longing for dead football buddy Skipper. When both Maggie and Big Daddy accuse Brick of wanting more than friendship from Skipper, the explicitness of their accusations shows how far ahead of Hollywood 1950s Broadway was in its depiction of “sensitive” subject matter. Though there are three young children in the production, this is most definitely not a play for the kiddies.

The Neighborhood Playhouse’s announcement that they were reviving Cat On A Hot Tin Roof was big news in L.A.’s theater community and well over a thousand actors submitted résumés and headshots for the production. With so much talent to choose from, it’s no wonder that Schwind was able to come up with the phenomenal cast now bringing Williams’ complex characters to life.

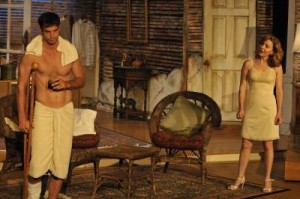

For the roles of Maggie and Brick, Schwind was looking for a pair of actors who could combine 1950s movie star looks and 2000s acting chops, and he struck gold in Kathleen Early and Aaron Blake.

Early, who starred opposite Kathleen Turner in the National Tour of Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf at the Ahmanson, makes a strong impression as the sexy, conniving Maggie. Act One is a virtual monolog for Maggie The Cat, Brick only occasionally interrupting the rants, pleas, and accusations of his frustrated wife, and Early doesn’t miss a beat. It is a dynamic, exciting performance, and also one that reveals the depth of Maggie’s pain.

Blake is new to the L.A. theater scene, but with the actor’s talent, classic good looks, and athletic physique (Brick plays much of the first act wearing nothing but a towel wrapped around his waist), he could very well find himself a star in the not so distant future. Blake shows us Brick’s sadness, repression, and regret, his passivity making Maggie’s frustration all the more palpable. Since Brick has a newly broken ankle, relies on a crutch, and falls a number of times, the part is a physically challenging one, and Blake is more than up to the role’s demands.

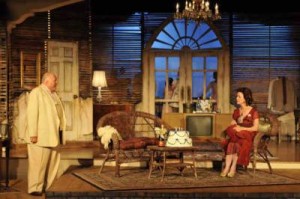

Michael Prohaska’s Big Daddy is truly bigger than life, the actor giving a Mississippi hurricane of a performance as a man with such a lust for life and power that his imminent demise is all the more poignant. The impression that Prohaska creates is so powerful that even when he is offstage his presence is felt.

Doing memorable, multi-layered work as well is Nadya Starr as the pitiable Big Mama, a woman who has loved (not wisely but too well) a husband who for the past forty years has had nothing but contempt for her.

Jennifer L. Davis is simply wonderful as Mae, lumbering around the stage in her final months of yet another pregnancy, a woman disheartened by a husband who’d be far more effectual if only he had a bit more of his wife’s raw ambition. Mark A. Cross does fine work as the unfortunately-named Gooper, the older brother who can’t seem to escape from the shadow cast by the taller, handsomer, younger Brick.

Completing the first-rate cast are Chris O’Connor (Dr. Baugh), Gordon Wells (Reverend Toooker), Beverly Oliver (Sookey), E Fé (Lacey, and child performers Hannah Kreiswirth, Becky Jester, and Rachelle Dale as Gooper and Mae’s obnoxious “no-neck monsters.”

The Williams estate could surely not be happier with Andrew Vonderschmitt’s gorgeous set design, integrated to perfection into the architecture of the 1927 Neighborhood Church. Just as Williams strips away the public façade of the Pollitt family, so Vonderschmitt strips off most of the plaster from the walls of their plantation, allowing us to see through to other rooms and to the sky beyond. Christopher Singleton’s lighting design is equally noteworthy, subtly enhancing the beauty of Vonderschmitt’s set and the changing moods of Williams’ script. Nancy Ling has designed a perfect ensemble of period costumes, exactly what the Pollitts would have worn on a summer evening.

Schwind has preserved Williams original three act-two intermission structure, and though the play runs well over two and half hours, it is never tedious or slow-moving. As much pleasure as there is in seeing a World or West Coast Premiere of a new work, there is great enjoyment to be had in revisiting a 20th Century classic like this one. At age 54, Cat On A Hot Tin Roof has stood the test of time, and contemporary playwrights can learn a lesson or two from a master like Tennessee Williams.

Neighborhood Playhouse, 415 Paseo Del Mar, Palos Verdes Estates.

www.neighborhoodplayhouse.net

–Steven Stanley

July 15, 2009

Photos: davidfairchildstudio.com

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY