“You’re a sad and pathetic man. You’re a homosexual and you don’t want to be, but there’s nothing you can do to change it.” Thus speaks birthday boy Harold to his party host Michael in Mart Crowley’s 1968 off-Broadway hit The Boys In The Band, to which Michael later replies, his voice laced with bitterness, “Show me a happy homosexual, and I’ll show you a gay corpse.”

With lines like these tacked on to memories of the play’s unrelentingly downbeat, self-loathing-filled 1970 film adaptation, it’s no wonder that The Boys In The Band has fallen out of favor in an era of ever-expanding gay rights and ever-burgeoning gay pride. Gay men have asked, “Is this really the image we want to see of ourselves? Is this really the “gay lifestyle” we want the homophobes to see … and use against us?”

Fortunately, with maturity comes perspective, and as more and more gay teens attend proms with their same-sex dates, and as more and more gay men and women marry, raise families and live their lives openly and proudly, it’s now possible to see The Boys In The Band without a sense of shame and to appreciate it for what it is—an honest, funny, gripping, perceptive, and powerful portrait of gay life before Stonewall—one that in many ways remains as true today as it was forty-two years ago.

It’s been far too long since Los Angeles audiences have had the chance to appreciate just how great, and timeless, Crowley’s comedy-drama is. For this reason alone, the Boys In The Band revival now playing at West Hollywood’s Coast Playhouse is news worth trumpeting. Add to that the enlightened direction of Jason Crain and the all-around sensational performances of its ensemble of nine and you have an important theatrical event not only for the gay community but for theater lovers of any sexual persuasion.

A quick reminder (or primer, as the case may be) on the play’s plot.

Harold, a “42 year-old, ugly, pock marked Jew fairy” has been invited to celebrate his birthday with a number of his closest friends at the upscale apartment of Michael, a 30ish gay man still struggling to accept his homosexuality. Also in attendance are Michael’s longtime friend and Saturday night bed partner Donald; heterosexually-married Hank and his lover Larry, the man he has left his wife for; Emory, a flamboyant butterfly with a sassy tongue; Bernard, an African American who finds himself a minority within a minority; and Cowboy, a prettyboy hustler hired by Emory as Harold’s birthday present. The catalyst for the evening’s turn of events is Alan, Michael’s now married college roommate, who arrives on Michael’s doorstep almost in tears, only to find his friend’s apartment filled with boys shaking their groove things to the strains of Toni Basil’s “Hey Mickey.” Since Michael has never had the guts to come out to Alan, it’s no wonder that the proverbial shit soon hits the fan, especially when a drunken Michael forces his guests to play a sure-to-be humiliating party game.

Yes, Michael’s conclusion that the only happy homosexual is a “gay corpse” is one that the post-Stonewall LGBT community has gone a great ways toward disproving. Notwithstanding, every one of these characters is alive and well and living in America today—maybe just not all in the same room. Times may have changed, but The Boys In The Band remains absolutely relevant theater and not at all the dated chestnut that some have accused it of being.

Director Crain clearly understands this, and has chosen, wisely I believe, to set the Coast Playhouse production in a nebulous time frame, sometime between 1968 and now. A 60s-attired cast might be more historically accurate, but a period setting would mean putting a too-safe distance between audience and play, making it all too easy to say, “Look how miserable and pathetic we used to be.” Sadly, there are still Michaels galore throughout the land, as any visit to Towleroad.com proves on a daily basis.

Another of Crain’s significant contributions to this revival is his insistence that these Boys In The Band be fully fleshed-out three-dimensional characters, people we can identify with and care about. He avoids the overwhelming negativity that permeated the film version from its opening scenes. This party starts out quite a fun place to be, and the laughter, at least in Act One, is just what one would expect from as clever and witty a bunch as are Michael and his friends.

Finally, Crain leaves us with an image (not in the original production yet faithful to its source material) that is so filled with promise that audience members are given a reason to cheer—and to leave the theater with hope in their hearts.

A production is only as good as its actors, however, and here too the Coast Playhouse is blessed. Having recently viewed the performances of the original off-Broadway cast in William Friedkin’s film adaptation, this reviewer humbly opines that the current stage cast tops the movie’s … and then some.

Matt McConkey simply could not be better as Michael. The key to McConkey’s superb performance is that he allows us in early scenes to see what a genuinely likeable chap Michael is, despite his many neuroses. It’s precisely because we like him so much that his alcohol-induced viciousness in Act Two comes as such a shock. This is why we care about him even as he attempts with considerable success to wound everyone around him. McConkey’s is rich, three-dimensional work, and we leave the theater with a compassionate understanding of Michael, and not merely pity or disgust.

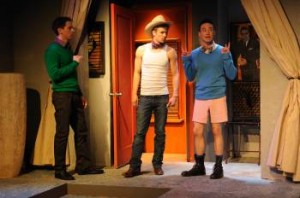

Chris Sams virtually reinvents the role of Emory, winning us over from the moment he sets foot on stage in powder blue sweater, bow-tie, pink Bermuda shorts, and hiking boots, with a flaming “All right this is a raid! Everybody’s under arrest!” On film, Emory is the kind of condescending stereotype that was all too prevalent in the Golden Age Of Hollywood. On stage at the Coast, Sams captures Emory’s infectious joie de vivre, shows us the loyal friend that he is, and lets us perceive the courage that has made him arguably the strongest of the Boys. I defy anyone in the audience not to fall in love with, and root for Sams’ Emory.

Eric Roth nails the plum role of Harold, spitting out catty remarks with the best and bitchiest of them, all the while revealing the pain hiding just below the surface. His performance here is every bit as splendid as his work as Buzz in Love! Valour! Compassion! a few years back, though Harold is as dark on the surface as Buzz was light. In both cases, Roth can hardly open his mouth without getting a laugh, and both plays are the richer, and funnier, for his presence.

David Stanbra makes Alan so much more than just a straight stereotype by showing us his character’s confusion, conflict, and inner torment. Darryl Stephens is a wonderful Bernard, sassy yet sensitive, and though he could up the volume a tad, I found his performance quite moving. Kerby Joe Grubb does excellent work as good-guy Donald, Michael’s sounding board at lights up and his most loyal friend at lights down. Sean Galuszka and Greg Siff (both terrific) make for an absolutely believable Hank and Larry, the couple whose budding relationship is the play’s greatest hope, and whose disagreements about fidelity are as relevant today as they were in 1968. Dustin Varpness plays the not-so-bright-but-damn-cute Cowboy with just the right mix of youthful sexiness, bravado, and cool.

Scenic designer Michael Fitzgerald’s nicely conceived set design manages to squeeze an appropriately timeless living room, entryway, and upstairs bedroom onto the Coast’s relatively small stage, and is made to look even better by Ellen Monocroussos’s excellent, mood-setting lighting. Marc Olevin’s sound design is first-rate, integrating a half dozen song hits from various decades, thus cleverly underlining the production’s deliberately vague timeframe. If clothes make the man, then costumes by Andraè Gonzalo are precisely the clothes choices these characters would make for themselves. Some snappy choreographed numbers are courtesy of Jamie Benson. Completing the design team are Sam Widaman (property design) and Michael Leddy (food stylist). (Leddy also serves as director’s assistant and Cowboy understudy.) Joe Fusco is production stage manager. Fight choreography is by Galuszka. Siff did the production’s excellent original artwork.

Under Crain’s direction and with a terrific cast bringing Crowley’s words to life, The Boys In The Band is Los Angeles intimate theater at its best. As relevant and important today as it was more than four decades ago, it’s also LGBT theater at its finest.

The Coast Playhouse Theatre, 8335 Santa Monica Blvd., Los Angeles.

www.play411.com/boys

–Steven Stanley

April 15, 2010

Photos: Nicholas Trikonis

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2025 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2025 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY