From the first lines of dialog in the Paul Lazarus helmed production of Of Mice And Men, it is clear that this will not be your usual version of John Steinbeck’s novella/play. The characters speak with a Hispanic accent rather than the usual Okie twang, and they interject Spanish por Dios’s and de veras’s in their speech. Lennie and other Salinas Valley workers wearserapes instead of jackets. And Bruno Louchouarn’ original music is played on a Spanish guitar.

Director Lazarus could just as easily have staged a traditional Of Mice And Men, but a bit of research revealed that the 1942 Bracero Treaty between the U.S. and Mexico brought countless Mexican citizens into the California agricultural sector. By situating the story a few years later (all the while keeping the original setting), Lazarus saw that a Latino-flavored Of Mice And Men would not only be historically accurate, but also prove the perfect vehicle for L.A.’s community of Hispanic actors and have particular resonance for today’s Los Angeles.

With stellar lead performances by David Noroña and Al Espinosa as George and Lenny, Lazarus’ decision has turned out to be a successful one, giving the two actors, as well as several of their costars, roles that they otherwise might have been passed over for.

The story remains the same. A pair of migrant workers arrive at a Salinas Valley ranch in search of work and it is clear from our first glimpse of them that there is something wrong with the big one, Lenny. His shorter, wiry compadre George cautions Lenny to not “do bad things like you did in Weed,” “things” that apparently got them run out of town. “Don’t say nothing when we go in to see the boss,” he warns Lenny, and makes the slow-witted giant repeat “I ain’t saying nothing” again and again.

Lenny, it seems, has a bad habit of killing small living things, not maliciously mind you, but put a mouse or puppy in Lenny’s hands, and chances are the poor creature will end up with its neck broken, the victim of a fit of childish temper.

This is not the only manifestation of Lenny’s childlike nature. He finds joy in hearing over and over how his and George’s life will change once they have saved up enough money to buy a house and a couple of acres, with a garden, and chickens, and rain in the winter, and soft rabbits that Lenny can tend.

Hired as farm workers, George and Lenny soon become aware that not all is right in this world of mostly men. Curley, the boss’s short-tempered, pugnacious son has married a “tart,” whose frequent visits to the bunkhouse, allegedly in search of her husband, have given the man good reason to be jealous. This “mean little guy” is more than a bit creepy. He keeps his left hand inside a Vaseline-filled glove, supposedly to keep the hand soft for caressing his wife.

“She’s purty,” declares Lenny when he first catches sight of Curley’s wife, immediately sounding alarms for George. It seems that the reason the two men had to leave Weed is that Lenny was accused of sexual assault by a woman whose red dress he had merely wanted to touch. When she started to scream, Lenny had tried to silence her, and she had cried rape.

With a woman like Curley’s wife in close proximity, there is too much danger of history repeating itself for George to feel secure, and in fact Of Mice And Men moves relentlessly towards its heartbreaking climax with the inexorability of a Greek tragedy.

If there is a problem with Of Mice And Men (or at least with this production), it is that no compelling reason is given for George to have stuck by Lenny time and time again. Over and over George says things like, “I could leave so easily if I didn’t have you on my tail” and “I can’t keep a job, and you lose me very job I get. You keep me in hot water all the time.” In fact, when the two men arrive in Salinas, the boss seems naturally suspicious of their relationship. Is George pocketing Lenny’s money? No, replies George, who claims (apparently falsely) that they are cousins. What kind of love, if indeed that’s what it is, makes George sacrifice so much of his life for someone who is clearly a millstone around his neck? There appears little likelihood of a sexual relationship between the two men, and it’s doubtful that 1937 audiences even wondered about such a thing. In 1937, readers might simply have stacked it up to the milk of human kindness. Contemporary theatergoers may need more explanation to truly understand and sympathize with George’s self-sacrifice and thus be fully moved by the tragedy of his final act vis-à-vis his friend.

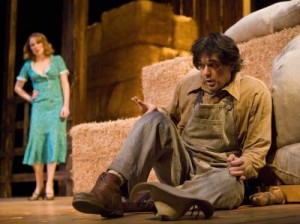

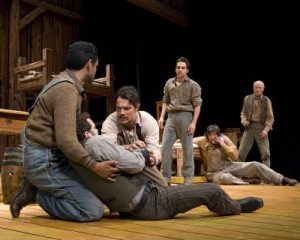

Still, there is nothing to fault in this Pasadena Playhouse production, beginning with the outstanding performances. Noroña’s impressive bio (TV, Broadway, musical theater (Frankie Valli in the first production of Jersey Boys), as well as co-writer/co-lyricist of Paradise Lost: Shadows and Wings) is more than borne out by the charisma and acting chops the actor displays as George. Even more remarkable is Espinosa as Lennie. The handsome and dashing leading man of the Playhouse’s Anna In The Tropics has disappeared absolutely and in its place is the hulking giant of a man with a gentle but dim-witted face. Though aided by padding under his costume and lifts in his shoes, the transformation is mostly due to Espinosa’s gifts as an actor, which are remarkable.

Of Mice And Men is at its heart an ensemble show, offering standout roles to most of the rest of its cast. Curtis C. steals every scene he’s in with a bravura performance as Crooks, the sympathetic African American worker whose only companions are books, since his white and Mexican co-workers will not associate with a n—–. (It’s a real shock to hear the ugly word uttered so many times, though its use is appropriate to the time and place.) Thomas Kopache is equally heartbreaking as Candy, the elderly worker who’s lost a hand and fears being cast out once he’s outlived his usefulness. A scarily effective Joshua Bitton makes Curley a dangerous loose cannon, Josh Clark does forceful work as “The Boss,” and Alex Mendoza is excellent as Slim, the solid “good guy” on the ranch. Sol Castillo and Gino Montesinos do well in supporting roles. Finally, Madison Dunaway reveals all of Curley’s wife’s conflicted longings, to be liked, to be wanted, to escape, and captures the distinctive look and sound of a young, not particularly bright 1940s woman.

The Pasadena Playhouse is the closest thing we have in L.A. to a Broadway house, not just in its classic architecture and proscenium glory, but also in the Class A design team with which Artistic Director Sheldon Epps consistently surrounds his actors. Scenic designer D. Martyn Bookwalter’s set is a wonder, its depiction of a bank of the Salinas river transformed in seconds into the solid, wood-planked walls and bunk-bed cots of a bunkhouse and later into a great barn. Lonnie Rafael Alcaraz’s excellent lighting sets the play’s diverse moods, as do Louchouarn’s sound design’s howling wolves and chirping crickets. Rita Salazar-Ashford’s costumes add a Mexican touch to the usual mix of early 1940s farmwear, and the dresses she’s designed for Dunaway are suitably “tartish” and just a bit out of fashion for 1942.

Paul Lazarus’ unique concept and solid direction make this Of Mice And Men unlike any other. It is an enthralling and entertaining evening of theater.

Pasadena Playhouse, 39 S. El Molino, Pasadena.

www.PasadenaPlayhouse.org

–Steven Stanley

May 20, 2008

Photos: Craig Schwartz

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2025 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2025 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY